Nostalgic Black history does a disservice to younger people. The community of my childhood wasn’t a haven. It was a battle ground.

We faced racial inequities being Black in White America and we also struggled with divisions within the Black community. That’s a part of Black history we need to be talking about, especially today.

As other marginalized groups in the U.S. and allies are finding common ground with Black people in the fight against racism and social injustices, the challenge is how to sustain the alliances. Our young people can benefit from hearing about the skills we developed confronting our intra-racial differences, not denial that those divisions ever existed.

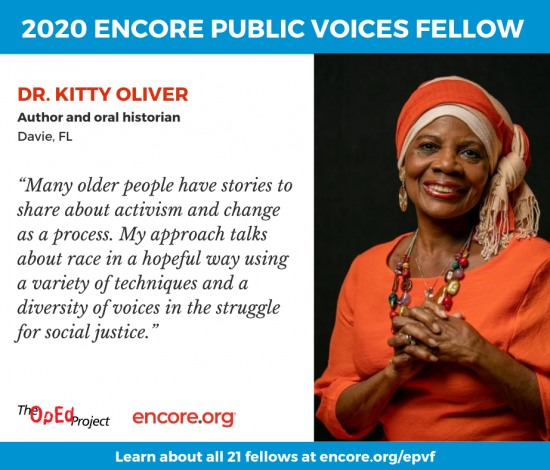

I grew up in segregation as the Civil Rights Movement was sweeping through the South in the 1960s, and eventually became one of the first Blacks to attend a large university and work for a major newspaper. I know the significance of telling inspiring stories of individuals and organizations breaking barriers and fighting against the odds. The Black firsts continue today, from the offices of vice president of the United States and the secretary of defense to the first Black student body presidents at prestigious largely White universities to the publisher’s desk of that same newspaper where I once worked. Highlighting achievers – past and present – gives people a sense of pride.

Nostalgic stories of a cohesive Black community until desegregation, on the other hand, are harmful to the younger generation. It distracts them from the work they need to do in a global society.

Conjure up an idyllic past in the midst of waves of police shootings, the rise of hate crimes and White supremacists, and the frustration of challenging systemic racism so pervasive it sometimes seems impossible to dismantle, and who wouldn’t want an escape?

As a race and ethnic relations oral historian, I’ve encountered this nostalgic recall as a common refrain in many of the interviews I’ve conducted with people of my generation, across cultures, for historical archives. They say: We never locked our doors. Everyone looked out for everyone else. We all got along. I’ve also mentored millennials with a passion for Black history working on projects to preserve the stories of elders and memorialize sites of significance in declining Black neighborhoods who say wistfully that they wish they were “back in the day.”

Certainly, in one sense, they face complexities we never encountered. Their Black experience encompasses a wide range of Caribbean, African, Latinx, Indigenous, and European influences. They may identify as people of color, or BIPOC, or mixed, or other. And the frictions that surface caused by the “my pain is worse than your pain” oppression olympics as Elizabeth Martinez coined it, add to the difficulty forming and maintaining alliances.

Black history, for younger people, doesn’t need to be nostalgic to be inspiring – even the troubling parts.

In my northern Florida neighborhood, the us-and-them rivalries showed up whenever relatives visited from far off places like Chicago or New York. They made fun of our accents, our dress, our dances, and our manners like they did the southern immigrants who had migrated North. The grownups accepted the fancy appliances they brought but raised an eyebrow when they boasted about life being so much better where they came from because, in truth, Black people in the big cities were struggling as well.

Jim Crow laws maintained the economic inequities and racial barriers to access and mobility in the larger society. We had finer lines of social separation within our race – most notably lighter and darker skin. Also, teachers had status and not domestic day workers, homeowners saw themselves better than renters, and single mothers were looked down on by two-parent households. And then there was the question of African ancestry.